P u b l i s h e d W e e k l y, N e w s, A r t s, & S t o r i e s F r o m T e x a s

Vol. 1, Issue 3,

Oct. 14, 2025

page 1

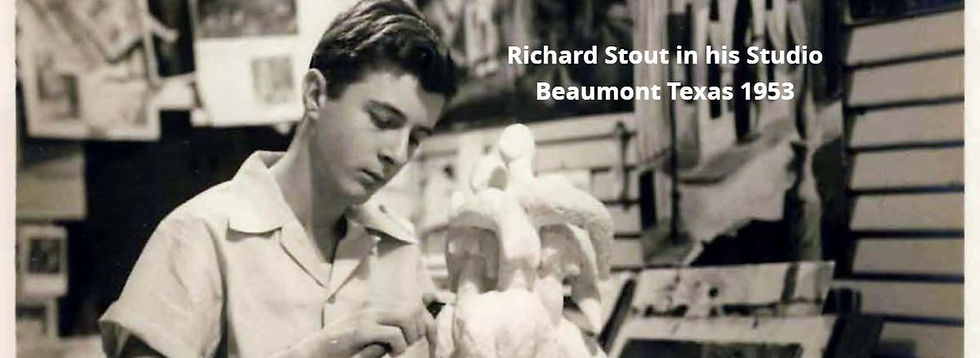

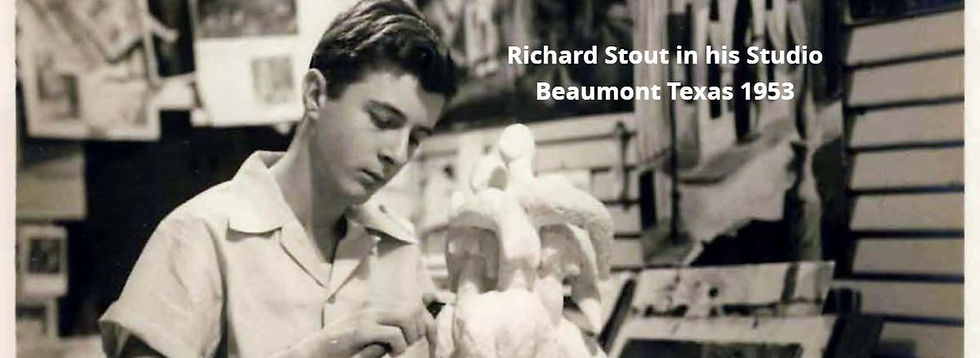

Richard Stout: The Watchmaker of Houston Modernism

Dan M. Allison, Mission News, Oct. 14, 2025

I first met Richard in the mid-1980s when he came for breakfast and to sit with his friends Dick Wray, Lucas Johnson, and Don Foster at Pat and Chet's 11th street café. Richard did not participate but the others taught me that real artists get good and pisssed before noon, take a nap, and paint long into the night. Every morning it was the same routine, and Pat would come to our table with a full round of beers at 9:00 in the morning, and we would proceed to empty their cooler of Shiner beers before lunch. The 11th St. Cafe sold more beer before lunch than most little garage-pool-table bars did in the Heights all day. This was an unbelievably valuable finishing school, where I really got a feel for the history of Houston's early art scene as well as learned my place in the moment when I mistakenly said something about “my career," and everyone just fell out of their chairs laughing. I had to buy another round, as Dick Wray leaned across to Richard and said the words that summed up they're deep friendship when Richard was going on and on about something, “Richard, I asked you what time it is, not how to make a watch” If you let him, Richard would take the stage and pontificate, until someone called a timeout.

I didn’t work with Richard Stout, until one afternoon in 2004 when he walked through the door of my printmaking studio, Texas Collaborative Arts on 11th Street. At the time, the place was buzzing. Terrell James and I had just finished a round of as-big-as-we-could-get monoprints. Rick Bartow had been in for his own series, New York’s Cora Cohen was collaborating with me long-distance, Nancy Kienholz and I were experimenting on my computer with lenticular graphics, and James McGee was building a digital collage edition. That was the spirit of the shop, a mix of experimentation, improvisation, and a refusal to follow the traditional rules of printmaking. Richard fit that spirit perfectly.

A New Kind of Collaboration

What began as a straightforward monoprint session quickly evolved into something far more complex, a multi-plate, color-separated photogravure project. Initially Richard struggled with the immediacy of making monoprints, and we had to come up with something else. Our first 3 mornings ended up with a predictable launch at the 11th St. Cafe, while we scratched our heads and tried to figure out where we could go with a printmaking project for Richard. We decided on polymer photogravures and used a scan from one of his recent paintings to create the matrix For his edition. Richard approached each technical problem as if it were an aesthetic riddle worth savoring. He was generous, articulate, and above all, curious. Working with him felt like being pulled into a long, intricate conversation about process, history, and the improbable intersections that make up a life in art.

Lunches were part of the deal. And if you were lucky enough to have lunch with Richard, you didn’t so much talk as listen. His mind worked like a web of tiny gears, each turning another, which is why Dick Wray’s old joke about the watch still held true. I thought back to the 1980s, when I was haunting the West Gray Street neighborhood, working on my own etchings at David Folkman’s Little Egypt Enterprises, I’d had the good fortune to meet Houston’s established generation, artists who had defined what contemporary art meant in Texas. Richard’s stories reached back another two decades beyond that, into the formative era of Houston modernism.

The Early Years

Richard Stout arrived in Houston around 1960, a young painter from Beaumont, already steeped in color and space, drawn toward abstraction. He had studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, lived briefly in Mexico City and San Francisco, and absorbed a global sense of what painting could be. But his roots in Texas, and in that distinctive light and humidity of the Gulf Coast, never left him.

In a 17-page narrative found later in his archive, he recounts how his mother, Bess Stout, discovered the house on Bonnie Brae Drive in 1963 “while going to get fried chicken.” That house would become his home and studio for the next fifty-seven years, a one-man citadel of painting in the heart of Houston.

The stories that unfolded from the documents I was archiving connected him to an astonishing array of figures: Dorothy Hood, Jack Boynton, Dick Wray, John and Dominique de Menil, early Museum of Fine Arts directors James Johnson Sweeney and Philippe de Montebello, patron Bill Lasiter, and gallery owner Kathryn Swenson. They were not merely names but the scaffolding of a new cultural identity in Texas, and Richard was there, brush in hand, as it was being built.

Bridging Generations

When I hosted an exhibition for him at Nau-haus Gallery in 2009, I realized how completely he bridged the first and second generations of Houston’s contemporary art movement. He wasn’t an outsider looking back; he was the connective tissue, the living archive linking the 1950s pioneers to the restless innovators of the 2000s.I had visited his home a few times, usually for one of his informal “house shows,” but it wasn’t until late 2019 that our paths crossed again in an unforgettable way.

Glenwood

I was at Glenwood Cemetery, doing something I probably wouldn’t have done without a woman’s persuasion, attending a guided tour of the graves. Richard was there, too, moving slowly across the uneven ground. He looked unsteady. As he passed in front of me, I felt that odd premonition that something was about to go wrong. A few steps later, he lost his balance, and I caught him as he fell back, and before he hit the ground. It was a small moment, the kind that sticks. I thought, Oh no, not him too.

By then, I was in that age bracket where funerals had become part of the social calendar. Many of the figures who had defined my early years, David Brauer, Nancy Kienholz, Jim and Ann Harithas, Marshall Lightman, Perry House, Dick Wray, were gone. Even the gamblers of Birraporetti’s Lucas Johnson and Bob Camblin, who could out-bluff me at liar’s poker while mocking my “art career”, had passed into legend.

The Studio Visits

After that day at Glenwood, I began visiting Richard almost daily. His studio was only a block from my own home, and I started photographing his work, cataloging it piece by piece. He was in reasonably good spirits, though plagued by a condition that caused his blood pressure to drop suddenly, sending him crashing to the floor without warning. Once, I asked what it felt like in those few seconds before he fell, whether he had any time to react. He said nothing, raised an eyebrow, and brushed a pile of books off the table between us. That was his answer.

We shared a birthday, just two days apart, his on August 24th, mine on the 22nd, and we’d planned a joint party. I told him I’d get him a bright red football helmet for the occasion, something to keep his head safe from those falls. He laughed, and we went out for hamburgers at the 11th Street Café, just like old times.

The Long View

Richard’s understanding of art, and of Houston, was encyclopedic. He’d lived through the city’s metamorphosis from provincial outpost to international player. He remembered when Dorothy Hood wrote from Mexico City, warning that “the pickings are slim” and that “it’s harder to ask someone to pass the greatness than to pass the salt.” Her solution: “Well, we should start a revolution then!” In a way, they did. Houston’s postwar art scene became its own revolution, built on stubborn independence and quiet ambition. Richard was one of its most articulate voices. His 1965 painting Escarpment entered the Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collection under Sweeney’s directorship, a sign that local modernists were no longer just regional curiosities. They were defining the language of abstraction for Texas itself.

(Click On Image To Expand To Full Screen)

Friends, Patrons, and Witnesses

By the early 2000s, Richard had stepped away from the gallery circuit and begun hosting exhibitions at home. Those gatherings were legendary, part salon, part history lesson, and always crowded with old friends and new admirers. In 2006, I photographed one of those evenings: Gertrude Barnstone, Toby Topek, curator Sally Sprout, collector Bob Card, the room glowed with that particular blend of intelligence and mischief that defined Houston’s art world in its prime. Gertrude, another of my great mentors, had once told me during the Bosnian war that I had no choice but to act because “you know the roads.” That conversation led directly to the formation of Artist Rescue Mission and my six-week trek through war-torn Bosnia delivering relief supplies. Houston’s art community has always been like that, intertwined, morally awake, unwilling to look away.

Critical Acclaim

When Richard exhibited again at Nau-haus Gallery in 2009, Houston Chronicle critic Douglas Britt wrote that he “could kick himself for having missed” an earlier opportunity to see a two-person show of Stout and Boynton. Britt went on: “Stout’s paintings are so fresh and exuberant that I’m having a little difficulty remembering what else I saw. He’s hijacked the show, it belongs to him.” He also noted the sparse, theatrical hanging of the exhibition, paintings suspended several inches off the wall, casting dramatic shadows, “all but shouting ‘ta-da!’” For a critic known for his dry restraint, that was as close to a standing ovation as you could get in print. Richard’s later exhibitions, particularly those organized by William Reeves and now represented by Sarah Foltz Gallery on Westheimer, reaffirmed his position as one of the central figures of Texas abstraction. Foltz herself, trained under Julie Kinzelman, has done a remarkable job preserving and promoting his legacy.

The Passing of the Baton

Richard Stout passed away on April 5, 2020, at his home on Bonnie Brae Drive, the same house his mother had found fifty-seven years earlier. He left behind a body of work that moves effortlessly between serenity and storm, structure and improvisation. For those of us who knew him, or came to know him late, he represented something rare: continuity. He embodied the lineage of Houston art, not as a relic, but as a living bridge. When I think back to those lunches, to the stories that spiraled from Beaumont to Positano, from the Menil salons to our burgers on 11th Street, I realize that every word, every anecdote, was part of a single, intricate construction, a life built with the precision of a watchmaker.

Epilogue

In his earliest known pastel from 1946, a young Richard warns family members not to disturb him while he works. Even then, he understood that making art was not a pastime but a calling. His archive, now preserved and digitized, bears witness to that lifelong discipline.I sometimes joke that I’ve already spent too much time explaining how I’ve made a watch. But maybe, when it comes to Richard Stout, that’s exactly the point. The gears are still turning, in the studios he inspired, the archives he left behind, and the conversations that continue across Houston’s art community.